At the start of the 1980s, a new youth culture was emerging throughout Japan, especially in Tokyo. Global popular culture - most prominently American music and fashion - fueled these new customs and ways of living. At this same moment, hip-hop had formally established a creative kinship between Bronx originators and New York’s downtown avant-garde. This relationship would propel artistic renegades experimenting with flow, layering, and rupture, including Fab 5 Freddy, Afrika Bambaataa, and Malcolm McLaren, to global fame. As hip-hop started to go global by the mid-1980s, Japan would become one of its central sites.

This made sense because the same structures of feeling developed in New York around hip-hop percolated in places like Shibuya and Harajuku, captivating the likes of Hiroshi Fujiwara, NIGO, and Jun Takahashi. Hip-hop would prove to be the connective aesthetic and cultural tissue knitting together all of this youthful and cultural foment. Today, hip-hop and Japan have become inextricably linked, and both stand at the vanguard of global fashion, music, and culture.

Biggie and BAPE

The story of Shawn Mortensen’s famous 1996 photo of Biggie rocking a BAPE jacket revolves around a moment of improvisation. Biggie was a favorite subject of Mortensen’s and the two had scheduled a photo shoot. During the shoot, Biggie noticed Mortensen’s BAPE jacket, and asked Shawn if he could wear it for a photo. Biggie draped it over his shoulders, and an iconic photo was born.

Biggie liked the coat so much that he asked Shawn about it, and Shawn connected him with BAPE mastermind NIGO. At that time BAPE did not make their clothes in Biggie’s size, so NIGO wanted to create custom pieces. But NIGO didn’t move fast enough. Biggie died before any bespoke BAPE was created. In 2002 NIGO and Mortensen held an exhibition at the BAPE Gallery in Kyoto, Japan for the NIGO-backed release of Mortensen’s book It’s My Life…Or it Seemed Like a Good Idea at the Time. For the exhibition, Mortensen and NIGO turned some of the photos into extremely limited edition t-shirts. Of course, Biggie made the cut.

(L) Shawn Mortensen x Biggie photo, 1996; (R) BAPE Gallery x Shawn Mortensen Biggie Tee, 2002

The photo of Biggie wearing BAPE is an iconic shot that is now used to establish the hip-hop and fashion bona fides of BAPE and Biggie, respectively. There’s a variety of stories floating around the internet claiming the true story of this photo, most of them false. However, the connection between BAPE, Japanese streetwear, and hip-hop is so intertwined that nearly any retelling could be as probable as the next.

Before this moment, BAPE had yet to forge a connection with American hip-hop. The brand was influenced by hip-hop, and NIGO had styled several Japanese groups, but he had yet to break into the American market. It wouldn’t be until 2002 that NIGO would become fast friends with Pharrell, and BAPE would become a staple of A-list US rappers, hip-hop culture, and global fashion. However, the history of Japanese streetwear began almost 25 years before NIGO’s meeting with Pharrell and is directly tied to hip-hop.

Hip-Hop Comes to Japan

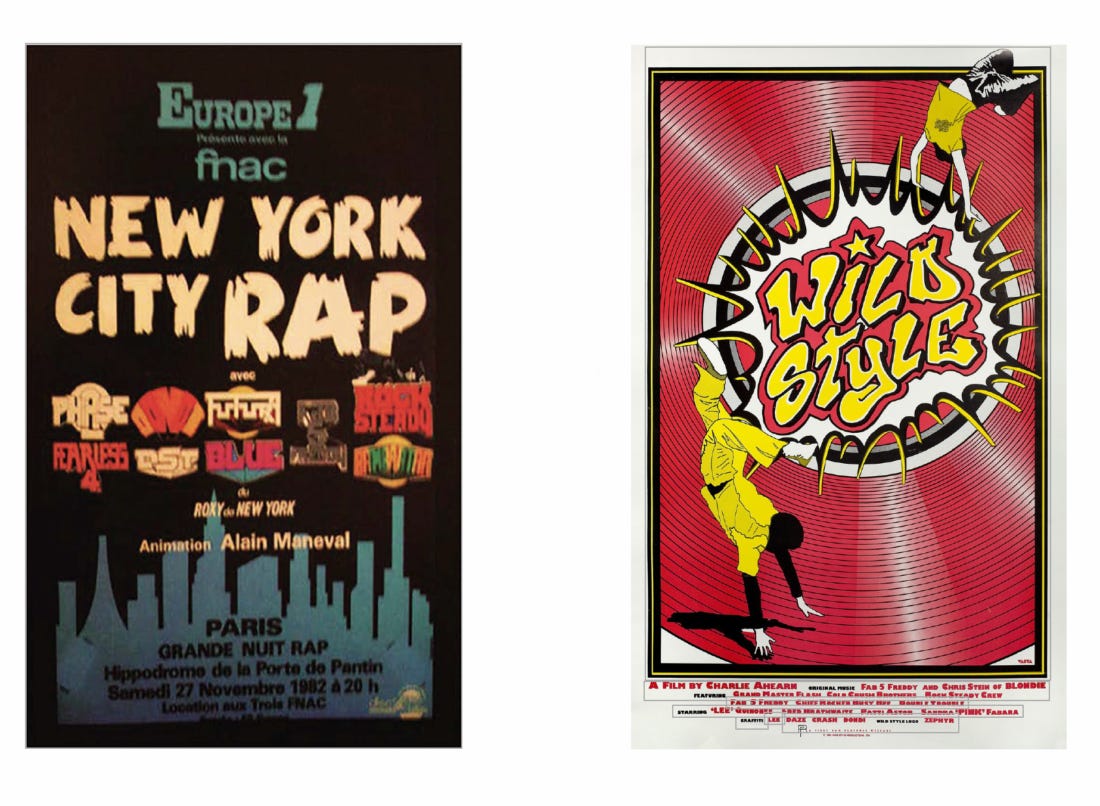

Hip-hop went global in 1982. In June the New York City Rap Tour hit France and London, and November witnessed the release of the first hip-hop feature film, Wild Style. Both events featured many of the same artists, musicians, and scenesters, including Fab 5 Freddy, Afrika Bambaataa, the Rock Steady Crew, DONDI, and FUTURA. Both events provided the template for hip-hop culture to come to Japan.

(L) New York City Rap Tour, 1982; (R) Wild Style movie poster, 1982

In November 1983, around 30 members of the Wild Style cast and crew traveled to Tokyo to promote the film during a month-long visit. The movie screened in a Shinjuku theater, the crew performed at several clubs throughout Tokyo, and appeared on TV. When they weren’t out promoting their film, the Wild Style crew set up their boomboxes and formed their own circle in Yoyogi Park in Shibuya. This is the moment when hip-hop truly takes root in Japan.

The Cold Crush Brothers performing in Tokyo, 1983 // photo by Charlie Ahearn

The Wild Style tour caused a sea change in Japan’s youth culture. Following the tour, b-boy crews such as the Tokyo B-Boys, B-5 Crew, and Mystic Movers suddenly appeared in Yoyogi Park, spilling over into the streets of Shibuya and becoming grist for Harajuku’s cultural and commercial makeover. Since the Wild Style tour, b-boys and hip-hop culture have been a key element of Yoyogi Park’s youth culture.

Contemporary b-boy battles in Yoyogi Park // tokyofashion.com

Hiroshi Fujiwara Discovers Hip-Hop

Hiroshi Fujiwara moved to Tokyo from the town of Ise in the Mie Prefecture in the early 1980s and quickly established himself as one of the coolest people in Tokyo. In 1982, he was voted “best dressed” at an underground party in Tokyo called London Nite, winning him a free trip to London. Fujiwara was deeply invested in punk and new wave fashion, and the trip allowed Fujiwara to meet two of his cultural and fashion heroes, Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren. Through the design and marketing of fashion and culture, Westwood and McLaren were key architects of the look and sound of punk rock, clothing and managing acts such as the Sex Pistols and the New York Dolls.

The following year Fujiwara returned to London and worked at the newest iteration of the couple’s store, World’s End. It was during this trip that McLaren told Fujiwara to abandon punk and new wave: the future was hip-hop. Following his own advice, McLaren would go on to produce the 1983 album Duck Rock featuring The World Famous Supreme Team, which in turn would provide the streetwear brand Supreme with their tagline and a 2009 collab.

Supreme x Malcolm McLaren, SS09

Before returning to Japan, Fujiwara made a quick jaunt over the Atlantic to visit New York and soak up the burgeoning culture at downtown NYC clubs such as The Roxy, Danceteria, and Negril. Again, Fujiwara is so cool that he’s credited with bringing the first crate of hip-hop records to Japan and teaching Tokyo’s club scene how to scratch and cut records with two turntables, a technique he learned in New York. Prior to Fujiwara, DJs at Japanese clubs would show up to spin and use whatever music the club provided. It was eye-opening when Fujiwara brought his records, playing the music that he learned was cool.

By 1985, he had formed Tinnie Panx (Tiny Punks) with Kan Tagaki. Tinnie Panx would go on to open for the Beastie Boys’ first run of Tokyo concerts in June of 1987. One year later, Fujiwara and Takagi connected with Haruo Chikado, founder of Japan’s first indie hip-hop label, BPM. Together, these three men established Japan’s first major hip-hop label, Major Force, under the Sony umbrella. By the end of the 1980s, a groundswell of DJs, MCs, and groups would emerge including Sha Dara Parr, Home Boys, Krush Posse, DJ Yukata, DJ Doc Holiday, and DJ Honda, all of whom stemmed from the global cultural work of Fujiwara.

Whether it was fashion, music, or culture, Fujiwara would continue to serve as Japan’s ambassador and conduit to global culture throughout the 1980s and beyond.

‘80s’ Babies

Throughout the 1980s, Fujiwara served as the ringmaster for a group of creatives that included Sk8thing, NIGO, Shinsuke Takizawa, and Jun Takahashi that ended up reimagining global fashion and culture. But before the cluster of creatives began to take shape, they were local tastemakers, DJs and musicians, and cultural curators that developed networks of cultural exchange with like-minded creatives across the globe. In effect, this group of young men was able to communicate a vision of fashion and culture to a Japanese audience that would pay dividends by the beginning of the 1990s.

This group was responsible for the creation of globally recognized brands and the promulgation of streetwear culture to Japanese audiences. Among the many projects this group executed, included the opening of the store Nowhere (Takahasi and NIGO, 1993), launching the streetwear brands Goodenough (Fujiwara, 1990 ), Undercover (Takahashi, 1993), NEIGHBORHOOD (Takizawa, 194), AFFA (Fujiwara and Takahashi, 1994), BAPE (NIGO, 1993), fragment designs (Fujiwara), and publishing a run of influential streetwear columns “Last Orgy” in the magazine Takarajima, “Last Orgy 2” in Popeye, and “Last Orgy 3” in Aasayan.

With every project they worked on, Fujiwara and his devotees were philosophically and practically aligned with hip-hop’s aesthetics of bricolage and pastiche. Inculcated in their deep love for street culture and music was a quicksilver ability to curate and combine–the best music, the best fashion, and the best that contemporary culture had to offer. And by 1993, out of the cultural flux and creation that followed in Fujiwara’s orbit, one of his disciples, NIGO, would decisively link the culture and style of streetwear, hip-hop, and Japan.

By the end of the 1990s, these ‘80s babies grew up and spun out a culture steeped in hip-hop from their base in Ura-Harajuku in Tokyo. They did so without appropriation or exploitation. They did it by recognizing the holistic and performative expression of identity bound up in hip-hop. Explaining this, Ian Gondry argues that Japan’s authentic embrace of hip-hop can be understood by the collaborative and improvisatory places known as “genba.” Genba–meaning ”actual site”–represent the spaces and places where the production and performance of hip-hop are negotiated. In Japan, this meant that hip-hop genba was at once rooted in African American culture, but was also responsive to local, Japanese concerns. American hip-hop filtered through the concept of genba resulted in meaningful transcultural exchange that only continues to grow deeper.

BAPE and Hip-Hop

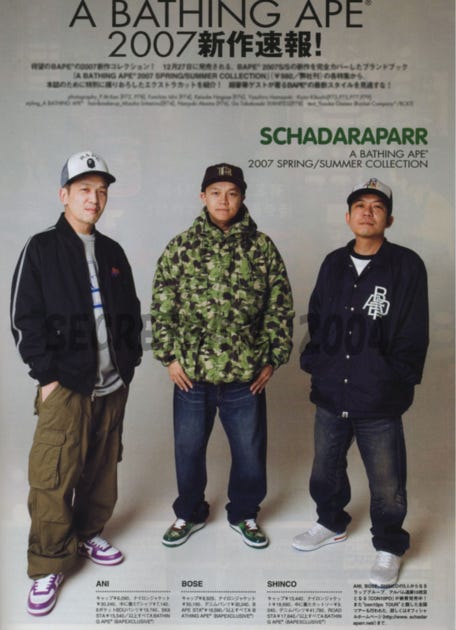

From the beginning, NIGO aligned BAPE with Japanese hip-hop culture and fashion. He made this decision both out of cultural appreciation and as a way to differentiate his brand from those of his friends and frequent collaborators within Fujiwara’s orbit. NIGO’s first move was to style his friends in the rap group Scha Dara Parr. They would go on to help break hip-hop into the Japanese mainstream with their hit song, “Kon’ya wa Boogie-Back” (Boogie Back Tonight).

Scha Dara Parr in the BAPE 2001 spring/summer e-Mook

NIGO also captured the burgeoning hip-hop zeitgeist with the group East End x Yuri. In 1994, East End x Yuri released the song “DA.YO.NE,” which would sell over a million records. From the start, NIGO styled Yuri Ichii, the group’s female MC, in BAPE. NIGO also connected with the rapper Cornelius and began supplying him with BAPE. In 1995, BAPE produced the full run of Cornelius’ tour shirts, further enmeshing BAPE with hip-hop.

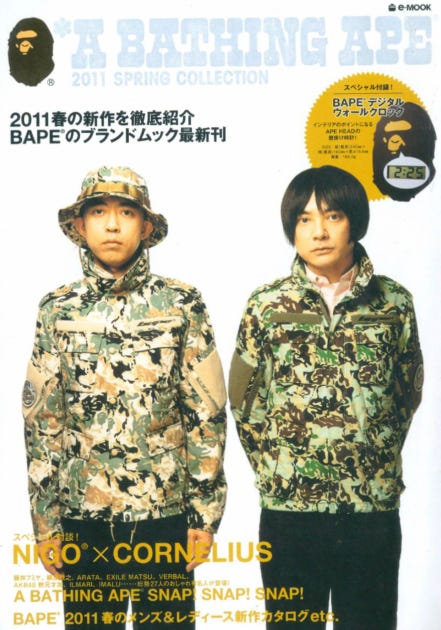

NIGO and Cornelius on the cover the spring 2011 BAPE e-Mook

While NIGO was growing BAPE through the Japanese hip-hop scene, he was also establishing international relationships. His first major connection was with the London trip-hop label Mo’Wax. After NIGO met label head James Lavelle, Lavelle became an ardent follower of BAPE. Additionally, BAPE established a relationship with Mo’Wax artists DJ Shadow and Money Mark. Through his relationship with Lavelle and the record label, NIGO was able to connect with graffiti artists STASH and FUTURA–the same FUTURA who first introduced hip-hop to Japan as part of the Wild Style tour–both of whom would ultimately become BAPE collaborators.

Beyond making important culture and business collections, NIGO was authentically an American culture nerd and fan of hip-hop. In 2000, he produced and released an album, Ape Sounds. For the album, NIGO recruited artists from Japan and the U.S. for an album that anticipates the sounds of NERD and Kid Cudi. Entertainment Weekly critic Will Hermes was duly impressed, writing, “this moonlighter should quit his day job.”

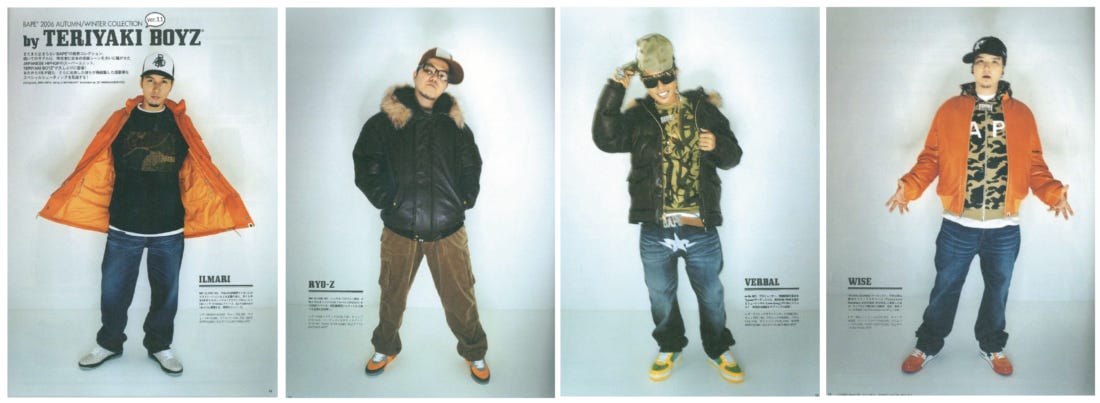

However, the biggest BAPE hip-hop flex would materialize in 2005 when NIGO formed the Teriyaki Boyz, consisting of group members Ilmari, Ryo-Z, Verbal, and Wise. Teriyaki Boyz would record for (B)APE SOUNDS, Star Trak, and Def Jam. When they released their second album, Serious Japanese, in 2009 they were able to pull features from Pharrell and Busta Rhymes. And of course, they were all dripping BAPE.

Teriyaki Boyz in BAPE 2006 winter e-Mook

In 2003, ten years after launching BAPE in Tokyo, NIGO and Pharrell Williams connected thanks to the insistence of Jacob the Jeweler. NIGO offered to let Pharrell use his Ape Studios to record while he was in Tokyo. The meeting and friendship between these two cultural omnivores now feels like it was preordained, but it came at a critical moment in the multidisciplinary careers of NIGO and Pharrell.

BAPE x Jacob the Jeweller collab

In 2004, Pharrell was working to make his fashion dreams a reality with his clothing line, Billionaire Boys Club, and shoe line, Ice Cream. With the help of NIGO and Sk8thing, Pharrell was about to make both Billionaire Boys Club (BBC) and Ice Cream a reality. In fact, NIGO helped Pharrell open a store above his BAPE Busy Work Shop in Harajuku. Pharrell returned the favor when NIGO opened up the BAPE NYC flagship store in 2005. Because of the relationship between Pharrell and NIGO, the shop became a mandatory stop for hip-hop. BAPE would become a hip-hop fashion staple. Everyone from Kanye West, Drake, Kid Cudi, Jay-Z, Mos Def, Clipse, Pusha T, and even the Beastie Boys, rocked BAPE or appeared in a BAPE e-MOOK (an e-Mook is a cross between and magazine and a book that includes a special gift). In fact, the first shoe that Kanye produced was a BAPE STA.

Kanye West College Dropout BAPE STA

Almost immediately after Pharrell’s cosign, BAPE started to show up in videos from hip-hop heavyweights. Beginning in 2004, BAPE featured in music videos from the likes of Lil Wayne, Snoop Dogg, A$AP Rocky, Soulja Boy, Clipse, and Juicy J, among others.

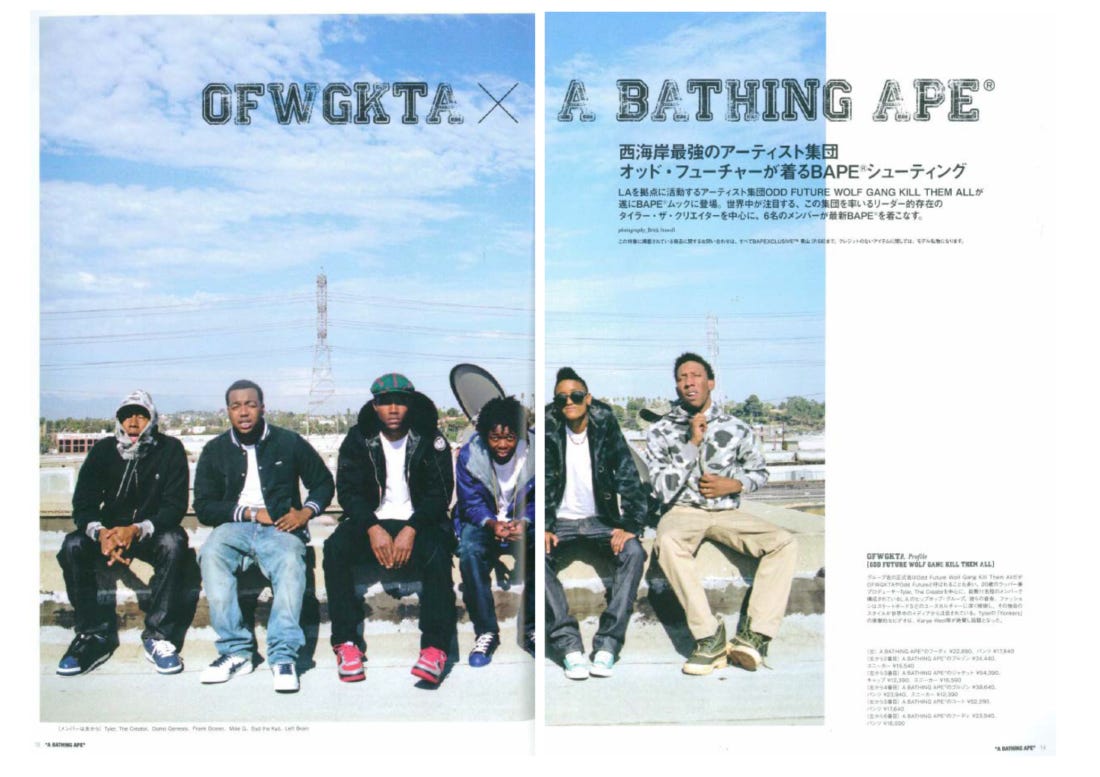

Not content to just rock BAPE, artists also worked the label into their songs. Some of the most notable lyrical shout-outs to BAPE come from Lil Wayne, Young Jeezy, Tyler, the Creator and Odd Future, and Drake and Future. Current hip-hop stars including Post Malone, 21 Savage, and Young Thug all reference the company. Even Cardi B referenced the brand in her breakthrough smash, “Bodak Yellow.”

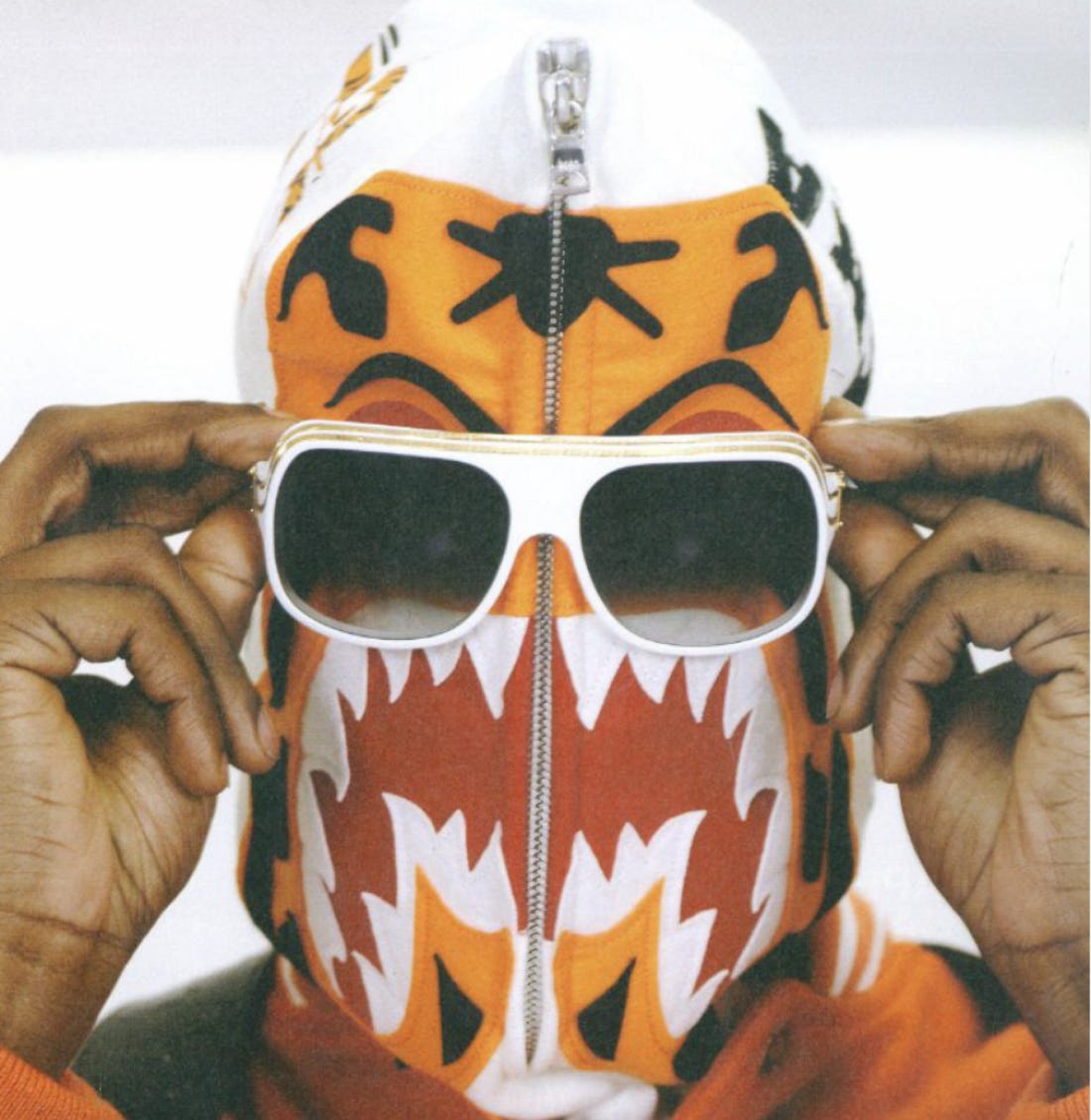

Odd Future featured in BAPE 2011 winter e-Mook

Continuing in the long line of hip-hop beef, BAPE featured prominently in the bad blood between Lil Wayne and Pusha T for the better part of the 21st century. This feud is classic hip-hop because it features money, clothing, and, of course, music. It all began in 2002 when Lil Wayne and Baby featured on the remix of the Clipse song “Grindin’,” and the Clipse reciprocated, guesting on Birdman’s song “What Happened to that Boy,” which was produced by longtime Clipse affiliates The Neptunes. According to Pharrell, Birdman–Cash Money Records founder and home of Lil Wayne–failed to pay The Neptunes for their work. Pharrell vowed to never work with Birdman or Cash Money Records again.

In addition to music, Pharrell and Pusha increasingly became involved in fashion through the influence of NIGO, with BAPE and Pharrell’s NIGO-backed BBC becoming sartorial staples of the rap cognoscenti. Lil Wayne wanted to join the club, too. Circa 2006, Wayne asked for some Billionaire Boys Club swag, and Pharrell refused. Undeterred, Weezy flexed BBC in his “Hustler Muzik” video and rocked BAPE on the cover of Vibe in 2006. Lil Tunechi took it a step further declaring that he was responsible for making BAPE hot in a 2006 Complex interview, not Pharrell. Shots fired, indeed. Clipse responded with the ice-cold “Mr. Me Too,” calling out everyone trying to bite their style, which was seen as a subtle jab at Lil Wayne. In 2012, Pusha dropped all subtlety and went for the jugular with “Exodus 23:1,” trashing Weezy, Birdman, and the whole Cash Money Records operation.

Nothing earns your hip-hop stripes like being one of the main instigators in a top-tier hip-hop beef. BAPE earned its hip-hop credentials.

Japan and Hip-Hop Today

BAPE continues to be a global brand with a global reach, especially when it comes to hip-hop. Since NIGO and Pharrell, the mutual admiration and cultural reciprocity have become a full-fledged partnership between Japanese brands and hip-hop including Comme des Garcons, Visvim, and Evisu, among others.

Freely reveling in the cross-cultural admixtures at home in hip-hop and streetwear, BAPE and UGG released a capsule collection that included mittens, BAPE STA sneakers, and a coat. For the lookbook, they tapped longtime fan Lil Wayne. “Been rocking UGG and BAPE since the beginning.” Weezy said in the press release, “This collab is next level.”

A$AP Rocky’s brand AWGE recently collaborated with NEEDLES for a limited tracksuit capsule. One of the most fashion-forward figures in hip-hop, Rocky worked to produce an elevated take on the streetwear and hip-hop historical staple, the tracksuit.

At its core, BAPE, Japan, and the global cultural and capital ascendance of streetwear is rooted in hip-hop. Fujiwara, NIGO, and their confederates channeled hip-hop’s cultural style into something new, mixing streetwear and high fashion into something unexpectedly luxurious, yet decidedly hip-hop. Because the cultural milieu of young Japanese creatives coming of age in the 1980s and 1990s was so attuned to global popular trends, the arrival of hip-hop provided a set of cultural and aesthetic tools to make and express new forms of identity through music and fashion. Similarly, BAPE’s popularity within American hip-hop circles opened up new opportunities for the hip-hop nation to connect, and influence, world fashion. Following in the wake of Fujiwara, NIGO, and BAPE, and typifying the connection between fashion, hip-hop, and Japan, Virgil Abloh remarked, “BAPE is our generation’s Chanel.”